Written by Victoria Gresham | January 20, 2023

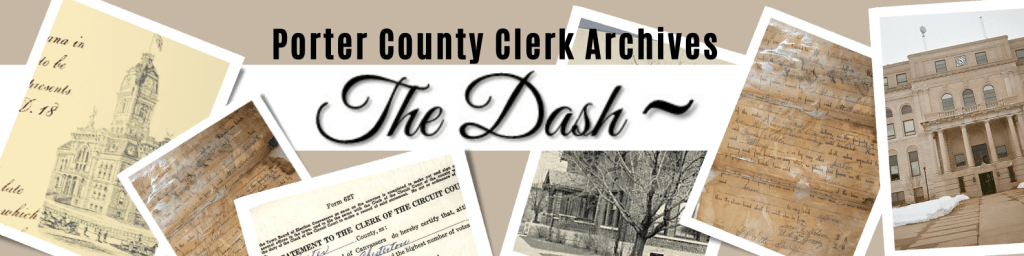

Coroners Inquest of James Call, May 17, 1900

One spring day on Friday, May 11, 1900, James Vincent woke to begin his day as any other. However, on this particular day, things would be different. His usual chores on the Beach Farm located north of the City of Valparaiso in Center Township would be unusually interrupted. Mr. Vincent would find himself in the presence of Jim Call, who had been on the farm set at north Franklin Street that morning. James offered Jim food and a comfortable place to stay in his home but Jim refused and preferred to stay at the barn. In his possession was a vial that remained with him while he stayed on the property.

The next day, Mr. H. M. Kyes had a visitor. It was Jim Call. His account of the meeting was as follows:

[*Transcript]

Deposition of Witnesses: The following is the testimony of the witnesses then and there examined before the Coroner, and which was then and there reduced to writing by the Coroner’s clerk _ in pursuance to the Statute in such case made and provided.

H. M. Kyes being duly sworn, deposes as follows:

On or about the 12th day of May 1900 the deceased came to my house and requested that I go with him to see his wife from whom he had separated. The reason he wanted me to go with him was that he was afraid that his wife would not let him in the house. I told him that I did not care to mix up with his domestic troubles but he insisted upon my going. I went finally. We had us trouble in getting in the house. The deceased said that he wanted to see his children. He talked with them and asked the oldest if she wanted to go and live with him. She replied that she did not but wanted to stay with her mother. He then bid them good bye and left the house. After he had left the house he said that it was pretty tough to have to leave his family and said further that I should not be surprised to hear of a suicide in a short time. He told me that there was another man between him and his wife that caused the trouble. He said it was the man who was boarding with them.

– H. M. Kyes

On Thursday, May 17th Mr. Beach unsuspectedly approached the barn on his farm. Then time stood still. Mr. F. H. Pike also arrived on the scene. He saw the body of the deceased laying on some straw near the West side of the barn. By this time, Mr. Beach had wrapped a blanket around the lower limbs of the deceased.

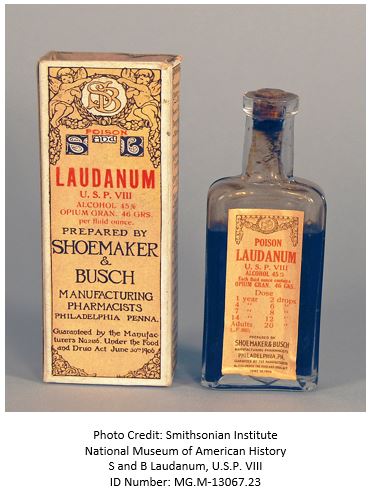

The four men were unaware how this day would join them together. Looking back, Mr. Vincent remembered his conversation the morning that he met James Call. He remembered the vial and how Jim referred to it as Laudanum. Mr. Vincent began searching for the vial as his thoughts ran through his head recalling every last word Jim uttered to what now appeared as instructions on how to find the missing vial. Finally in his hands, Mr. Vincent read the label which was marked from a druggist of Grand Crossing, Illinois. It was in that moment Mr. Vincent realized that James Call used the drug to kill himself.

As required by law, Fred G. Ketchum, Porter County Coroner was called to investigate the death of the deceased. Mr. Ketchum conducted his Coroners Inquest, which included the witness testimonies of James Vincent, H. M. Kyes, and F. H. Pike. Coroner Ketchum determined that James “Jim” Call came to his death by taking Paris Green with suicidal intent on May 16, 1900. The body of Jim Call was later transported to the undertaking room of the Bartholomew Funeral home located in Valparaiso, Indiana.

Paris Green – the Silent Killer

In the Victorian era, one of the deadliest poisons available was known as “Paris Green,” which was used as an insecticide by French grape growers in the 1870s. However, its first success in pest control began in the Midwest crop fields of the United States in 1860 against the Colorado potato beetle. Paris Green was a chemical result of copper acetoarsenite widely used to eliminate pesky insects in fields and orchards.

Paris Green, also known as emerald green, or its family hue cousin Scheele’s green, being the first of its kind, would become the silent killer ending lives on both sides of the Pacific Ocean between 1837-1901, which spans the 63 year reign of Queen Victoria. The Victorian British Empire ruled the globe, with goods and products, such as calico cotton and lustrous green fabrics and wall coverings being multidirectional between Britain and its colonies. Such products including, paint, wallpaper or dyes largely made it into the homes of Britain’s social elite to the pioneers and rustic homesteaders of America, whose inhabitants unknowingly welcomed in this silent killer.

Through medical examinations and scientific discoveries, we now know that arsenic is a highly toxic substance that causes skin lesions, vomiting, diarrhea and even cancer. In the 19th century, it made its way to the general public being marketed and camouflaged on the shelves in candy, toys and medicine. In spite of the health dangers of the poisonous gases from the arsenic-laced wallpaper, synthetic green dyes didn’t come onto the scene until the 1870s. Even with scientific evidence of its highly toxic nature, production of emerald green paint, which was considered a regency pigment, was not banned until the 1960’s.

Laudanum – the Liquid Wonder

Another pain medicine widely used in the “olden days” was known as Laudanum, which was a liquid mixture of opium and alcohol. It was first developed in the 17th century by Thomas Sydenham, an English physician. By the time it reached North America, it was commonly used to prepare patients for surgery. Laudanum was used to treat and cure many health issues ranging from urinary complaints, diarrhea to even its most common use as an analgesic for young children. The opium concoction was mostly used by women for female disorders, headaches or bouts of melancholy. Mothers and caregivers often dispensed it to crying teething or fussy children to calm their moods. However, grave mistakes in offering high dosages to young children often resulted in death. Men on the other hand, found their pain relief mostly by consuming alcohol.

Unfortunately, many intentional and accidental overdoses of laudanum claimed the lives of many Americans leaving no one immune to its fatal effects. Laudanum is no longer available under the name “tincture of opium” but it is still sometimes used to treat diarrhea. Over the centuries, laws have been created to help regulate these addicting drugs. Opium painkillers have a history in America as far back as the founding of the country itself. During the American Revolution, the Continental and British armies frequently used opium as a quick drug to heal the sick and wounded soldiers. It was not unusual for physicians to prescribe the opiates for a wide range of health issues nor was it uncommon for individuals to self-medicate their ailments with opiate concoctions.

However, the dark side for many people during the Victorian Era was the easy access that these silent killers offered to a distraught individual that sought instant relief or to end a life. By the late 1890s, the medical field began warning physicians of the overuse of opium and the effects of morphine addiction. While enacted legislation has played a key role towards regulating narcotic use, the Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914 became pivotal to how physicians would practice prescribing opiates. Today, modern doctors have more treatment options than their 19th and 20th century counterparts. Regardless of the available drug intervention clinics, regulated prescription policies, and access to suicide hotlines, the war on opiate and narcotic addictions still remains to be a public health issue nationwide.

References: http://www.sciencedirect.com/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/paris-green; http://www.narconon.org; http://www.chemist.ca; http://www.esquiremagazine.com; http://www.Brittanica.com; http://www.smithsonianmag.com; http://www.janeaustensworld.com; http://www.harpweek.com; http://www.americanhistory.si.edu/collections

(*) Transcription by Victoria Gresham, Porter County Clerk Archives, January 17, 2023