Written by Victoria Gresham | March 13, 2023

When the Bell Tolls and the Whistle Blows

The town clock struck six. The hustle and bustle of everyday people could hear the Catholic bell ringing in the background. However, there was one sound no one expected that resonated over it all. Twelve eye witnesses recalled the dreadful event that occurred between 6:00-6:30 P.M. on Saturday, June 28, 1890 at the railroad crossing of Napoleon St. located in Valparaiso, Indiana.

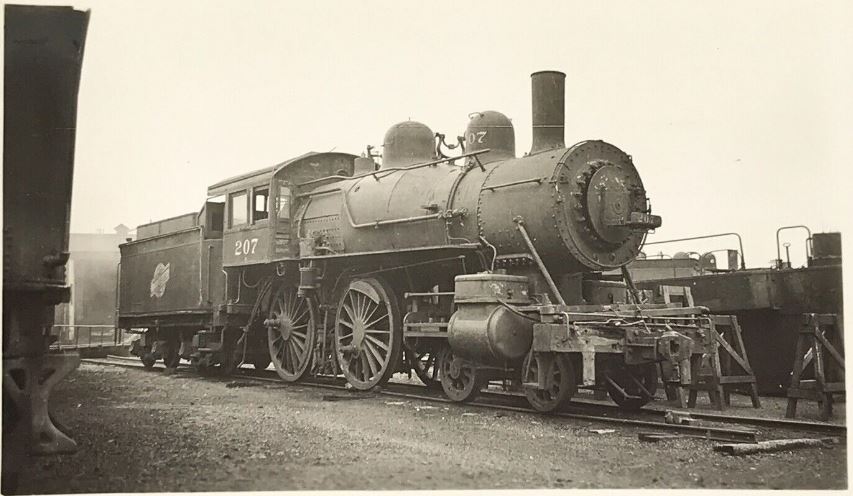

John C. McCarthy was the engineer that day. The Fort Wayne road carried two types of transport- a coach train and a locomotive that were employed in conveying workmen from Wanatah to their destinations in the sand pits near Clark Station. The laborers would ride the rails in the evening to return back to their homes. The coach train was side tracked at Wanatah and the locomotive backed in at Valparaiso to be housed for the night.

Reports state that two family members were on their way home traveling in a horse and buggy when they had approached the track. The Pittsburg, Fort Wayne & Chicago Railway Engine No. 207 struck the carriage with such force and impact that both passengers were thrown out onto the track.

(Image Source: Chicago & North Western RW Tr. Eng. Loc. No. 207, Robert Graham Collection, 1981)

The driver was identified as George S. Wood, a young single man of light complexion, 5 feet 8 inches high and dressed in citizen’s clothes. His body was carried to the Continental Hotel, where he held on to life by a thread. The second passenger was his widowed mother known as Mrs. Mary Wood. She was thrown to one side of the track and surprisingly escaped death surviving with injuries to the head. Her unconscious body was also transported to the Continental Hotel where it was expected that she would recover from her injuries.

William Robinson witnessed the accident. H. C. Coates, M.D., Porter County Coroner investigated the accident diligently questioning eye witnesses to the incident. Mr. Robinson obliged. Only minutes earlier, he rode past Mr. Wood, and since not meeting him very often, he had turned to look back at George. George’s buggy and team of horses were “trotting right along in a prudent manner when he had passed” Mr. Robinson. It was less than a minute afterwards that William heard the crash. He saw the engine strike the buggy throwing it approximately sixty or seventy feet westward. By the time he made it to the scene, George Wood was nearly a hundred feet west of the crossing.

The train was running backwards when William saw it run across the road and then out of sight. He did not see the train when he had crossed and thought it must have been running about twenty five miles an hour at the time of the crash. William testified that the road was pretty well blocked with a long string of box cars on the east of the crossing, on the north track making it impossible to see the approaching engine.

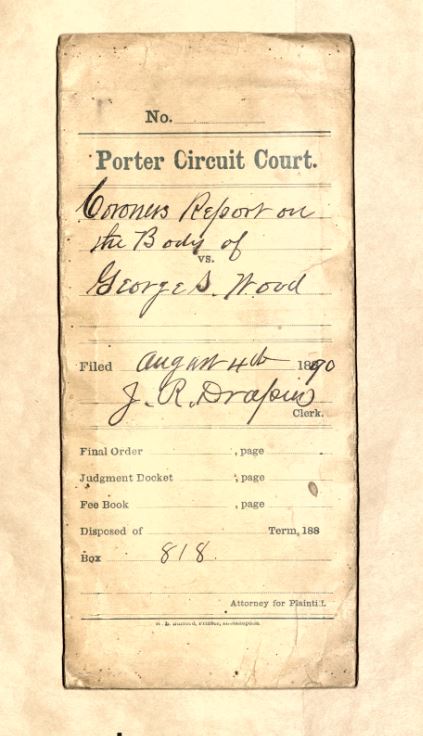

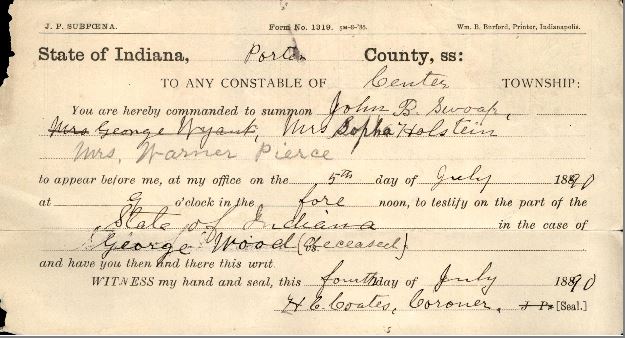

(Image Source: Porter County Clerk Archives by Victoria Gresham, March 2, 2023)

“Did you look east at the time you crossed the road?” asked Coates, “Did you notice any train coming?”

“Yes,” said William, “I saw no moving train.”

“How far was the distance that you could see up that track?” responded Coates.

“I think it was from a quarter to half a mile,” Robinson replied.

Although William heard a bell ringing before he got to the track, he was positive that there was no bell ringing when it struck George Wood’s buggy nor was there a flagman posted at the crossing.

Another witness, G. W. LePell, saw the flagman leaving his post at 6:20 PM. He recalled seeing the engine traveling west with coal cars on the south side of the track, while the north side had box cars and refrigerator cars with a high top to them.

Upon strike, the team of horses broke loose, broke the double treet and tipped the buggy over causing it to slide along the rails as the team jerked away. The team was not injured except a piece of skin being torn from the thigh of one horse. George was jerked up on the dash board of the buggy and as the buggy tipped over he fell out onto the track. He then struck the rails as he came down. The locomotive engine passed over him while the ash box of the engine seemed to catch him and drag him out of sight. Mr. LePell grabbed the team but could no longer see George.

“The watchman often made the remark that they would kill somebody at that crossing if they not protect it,” stated Mr. LePell.

John P. Swoap lived near the Fort Wayne road when he saw the engine run by. “I road down in a buggy with my brother-in-law Mr. Hayes,” he began telling Coates, “as I got down just about in front of the shop the engine went past and in a moment or two I heard the crash at the crossing, and the thought struck me that there was something hit there, and I put my basket in the shop and went down there, and just as I went down on the track, and a man passed and I says what’s the trouble and he says there is somebody killed up there, and then I saw the buggy laying at the side of the track at the west of the road crossing.”

Mr. Swoap immediately saw the mangled body of George with one arm torn to pieces laying ten feet or so further west of the buggy. The sight was hard to take in and he could not look at him anymore.

Mrs. Maggie Pierce lived west of Monroe Street and was in her kitchen preparing supper at the time of the accident. “I went from the kitchen to throw out some water,” she recalled, “and I saw the train coming at an awful speed, and I just throwed the dish pan on a nail at the door, and I heard an awful crash, and I went to the west window and I looked out and saw the spokes and pieces of buggy flying, and I run out the front way and down to the railroad and saw what happened.”

(Image Source: Porter County Clerk Archives by Victoria Gresham, March 2, 2023)

“How far was the engine where it stopped from where they [passengers] lay?” questioned Coates. “As far as across Washington Street,” she replied.

George sustained remarkable injuries from the crash having been thrown eighty to a hundred feet. His arm was smashed with the bones protruding out; his head had a hole in the back of it with a badly bruised back. Mary Wood had a cut on the side of her cheek and her ear was cut as she laid east of George on the ground unconscious.

H. C. Coates, M.D., Porter County Coroner continued to review the chain of events, including that of John C. McCarthy, locomotive engineer. McCarthy had served in his position with the Pennsylvania Company operating the Pittsburg, Fort Wayne & Chicago Railway for ten years. Coates was steadfast with an exhaustive exchange of questions for McCarthy, who explained the events as follows:

“I was backing west with engine #207 at a rate of speed not exceeding four miles per hour. When within ten feet of Napoleon street crossing, I saw a team crossing the track with a carriage attached. I applied the air brakes and reversed the engine and stopped one engine length from where I struck the carriage. I got off the engine and found a man laying between the rails on the track. The man was unconscious but not quite dead. His right arm was mangled and he had his clothes torn off. I was informed that his name was George S. Wood, a resident of Porter County, Indiana; Mrs. Mary Wood was laying about five feet outside the track, also in an unconscious state.”

(Image Source: Porter County Clerk Archives by Victoria Gresham, March 2, 2023)

Coates questioned the locomotive’s speed that McCarthy had claimed. He further questioned why McCarthy did not blow the whistle. “The rope was detached,” McCarthy said, “I could not blow it.” Although McCarthy stated that he was ringing the bell that evening, he did indicate that there was no watchman at the time of the accident and the view was obstructed between the engine and the carriage buggy due to the box cars on the north side track.

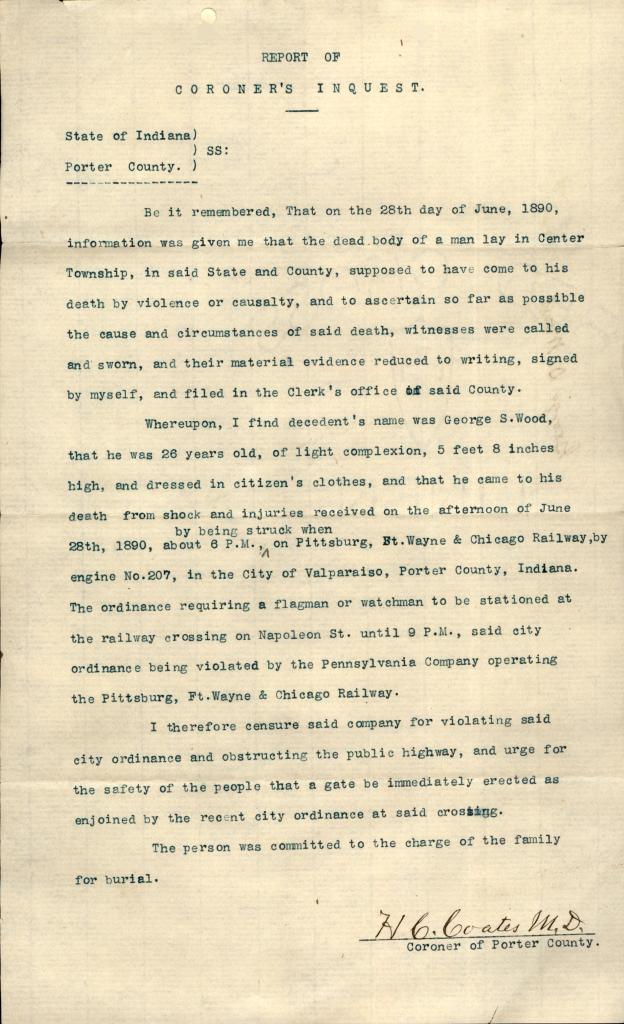

Upon completion of his examination, H. C. Coates, M.D., Coroner, thereby had censured the railway company for violating the city ordinance and obstructing the public highway. Coates concluded that “the ordinance requiring a flagman or watchman to be stationed at the railway crossing on Napoleon St. until 9 P.M., said city ordinance being violated by the Pennsylvania Company operating the Pittsburg, Ft. Wayne & Chicago Railway.” It was further “urged for the safety of the people that a gate be immediately erected as enjoined by the recent city ordinance at said crossing.”

George S. Wood and his mother, had made their home on a farm near Salem, south-west of Valparaiso. Mary didn’t know her fate that day would include feeling the familiar pains of agony and grief. George died at the age of 26 years old having passed away only minutes after his arrival at the Continental Hotel and close to half an hour after the initial impact with Engine No. 207.

(Image Source: A. G. Hardesty, Continental Hotel (1876); by Shook Photos)

The complete Coroner’s Inquest witness of testimonies included that given by the following:

John H. Knight, locomotive fireman

William Robinson, farmer

G. W. LePell, gas works employee

John M. Merrill

John P. Swoap

Mrs. Sophie Holstein

Mrs. Maggie Pierce

John Nestor, farmer

Michael Welch

Jerome Massy, farmer

and Mrs. Mary E. Wood

Next time you cross the Napoleon track, take a moment to remember that young man named George S. Woods.

References: Porter County Clerk Archives, Coroners Inquest of George S. Wood filed on August 4, 1890; The Tribune Newspaper, Volume 7, Issue 12, Publication Date July 3, 1890