Written by Victoria Vasquez | March 7, 2024

There’s Gold in Them Thar’ Hills

The news of gold in California brought over 300,000 people to the west coast from around the world and across the United States. San Francisco, California was a hot spot in 1842 being a settlement of 200 people to a boomtown of over 36,000 by 1852 with the news of gold spreading far and wide.

In 1849, at the height of the gold rush, news of gold reached the ears of Erban Preston of LaPorte County, Indiana, who then reached out to Edward Flinn of Porter County, Indiana. The effects of the gold rush were substantial as prospectors traveled west by land and sea.

The excitement for wealth and prosperity started in California when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California on January 24, 1848. James was a carpenter and saw mill operator who was employed by Johann (John) Sutter to build his saw mill. He entered in a partnership with John Sutter after losing his ranch. James had volunteered during the Mexican-American war only to return to his home in 1847 to find all his cattle gone leaving him with no source of income. This change of events left him to rely on other skills to make his living. Little did he know what was ahead.

In exchange of providing his supervision over the construction of the sawmill, James would receive a portion of the lumber. Then one morning, on January 24, 1848, Marshall noticed something odd in the channel bed near the work site; the foreign objects were shiny flecks and a familiar substance to him.

“I picked up one or two pieces and examined them attentively; and having some general knowledge of minerals, I could not call to mind more than two which in any way resembled this, iron, very bright and brittle; and gold, bright, yet malleable. I then tried it between two rocks, and found that it could be beaten into a different shape, but not broken. I then collected four or five pieces and went up to Mr. Scott (who was working at the carpenter’s bench making the mill wheel) with the pieces in my hand and said, “I have found it.”

“What is it?” inquired Scott.

“Gold,” I answered.

“Oh! no,” replied Scott, “That can’t be.”

I said,–“I know it to be nothing else.”

— James W. Marshall

James Marshall shared his remarkable discovery with John A. Sutter and the men tested the flakes to confirm their find was indeed the precious mineral. At first, the men hoped to keep the discovery a secret to protect their plans of the envisioned sawmill. They knew if word got out it would disrupt their future lumber business. The business partners didn’t want to risk losing their investment in the mill. Soon the discovery of gold in Coloma, California spread like wild fire throughout the new frontier and around the world. The impact became known as the “California Gold Rush.” The effects it had were substantial on the surrounding inhabitants since it was credited to the forcing out of the native indigenous societies from their land as gold-seekers flocked in like groves. These gold prospectors were known as “Forty-Niners,” which referred to the year of 1849 when the Gold Rush started.

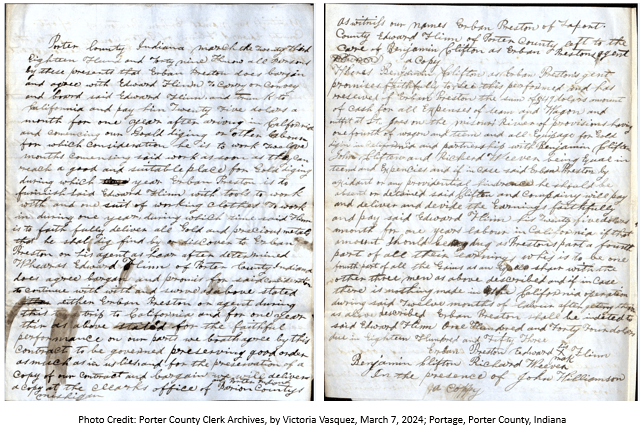

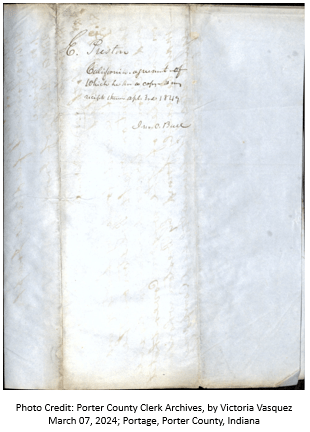

Erban Preston was no different then the rest of those seeking to strike it rich. On March 23, 1849, Preston entered in a partnership with Edward Flinn to join forces on their gold-seeking efforts. The men bargained and Edward agreed to travel to California in exchange that Preston would pay him “twenty-five dollars a month for one year after arriving in California and commencing their gold-digging and other labor for which consideration he is to work twelve months commencing said work as soon as they can reach a good and suitable place for gold-digging.” (Source: Preston California Agreement, Porter County Clerk Archives, Portage, Porter County, Indiana.)

Erban and Edward would be amongst some of the first Hoosiers to become gold prospectors. Other Hoosiers to follow in their footsteps would be a former California miner, F.F. Taylor, and R.L. Royse, an “Indianapolis gold and diamond prospector” along with “Uncle” John Merriman, who ventured out to the California gold fields in the 1880s. Gold was such a hot commodity that findings of this precious metal started appearing in Indiana creek beds that one man known as “Wild Bill” or by his given name William E. Stafford, became the “Hercules of gold-digging” as he panned the creeks of Morgan and Brown counties in Indiana.

During that first year, Erban Preston was to furnish Flinn “with tools to work with and one suit of working clothes to work in during one year” during which time said Flinn was to fully deliver all gold and precious metals that “he shall dig, find by or discover” to Erban Preston or his agent as often determined. The men further agreed as follows: “Whereas Edward Flinn of Porter County, Indiana does agree, bargain and promise for said consideration to continue with and swear as above stated either Erban Preston or agent during this trip to California and for one year this as above stated for the faithful performance on our parts we both agree by this contract to be governed preserving good order as much as in us lies, and for the preservation of a copy of our contract and bargain we will deliver a copy at the Clerk’s office of Berrien County, Michigan and Porter County, Indiana. As witnessed our names Erban Preston of LaPorte County, Edward Flinn of Porter County left to the care of Benjamin Clifton as Erban Preston’s agent a copy.”

With Benjamin acting as Erban’s agent, it would be his responsibility to ensure that Edward would have the resources for his journey. Benjamin had a key role as Erban’s right hand man to “promise faithfully” that all would go well.

He was entrusted with Erban’s money in the sum stated in the contract and bound to its terms defined below to wit: “forty-nine dollars amount of cash for all expenses of team and wagon and outfit at St. Joes on the Missouri River of provisions having one fourth of wagon and team and all equipage for gold digging in California and partnership with Benjamin Clifton, John Clifton and Richard Weever being equal in team and expenses and if in case said Erban Preston by accident or any providential hindrance he should be absent or detained said Clifton and Company will pay and deliver and divide the earnings faithfully and pay Edward him his twenty-five dollars month for one year labor in California if that amount should be dug as Preston’s part a fourth part of all their earnings whose is to be one fourth part of all the gains as an equal share with the other three men as above described and is in case there is nothing made in the Californian operation during said twelve months of labor after getting there as above described, Erban Preston shall be indebted to said Edward Flinn one hundred and forty-four dollars due in eighteen hundred and fifty three (1853).”

All those involved in the California operation included Erban Preston, Edward Flinn, Benjamin Clifton, Richard Weever, whose contract was signed in the presence of John Williamson.

As Edward prepared for his westbound trek, the contract made its way to the Porter County Clerk’s office whereas Erban Preston delivered it the morning of March 23, 1849 the sum of “$49 ¼ forty nine and 25/100 cts dollars and one hundred pounds of bacon as an effectual intrust in our entire outfit in company and traveling arrangements to California and equipage lacking one pick, an outfit at a reasonable conclusion. Benjamin Clifton [sic].”

The list of supplies for Edward’s trip included the following Bill of Items:

$500.00 Paid at Michigan City of supplies.

$20.00 Loan to be paid for provisions at St. Joseph.

$8.75 One quarter (1/4) of Wagon

$10.00 Four Team feed to St. Joseph

$1.00 Feriage

$0.25 Bolt of Iron

$1.00 For Pans

$12.50 Tent Cloth

$1.25 For Spade

An additional twenty-five cents was provided for paint to have the names of the partners, “Preston and Clifton” prominently displayed in “large and inteligable on the sides of the wagon cover that it may be easily found by Preston who is an equal stock holder with said company above described.” Covered wagons led by teams of horses or oxen were the typical method for land travel in those days until the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869. Until then, travelers could take up to 6-months of their lives at travel speeds of 8-20 miles per hour a day to reach the borders of California.

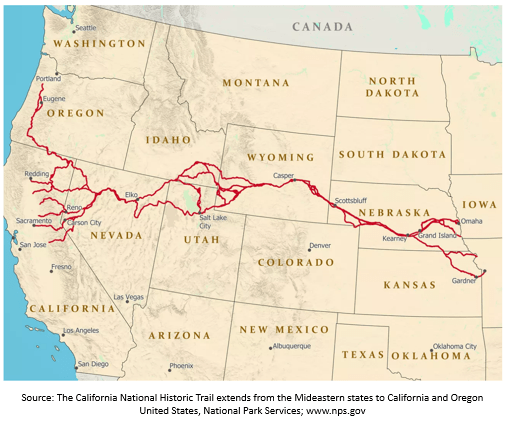

The three main routes used by American gold seekers were the Oregon -California Trail, the Cape Horn route, and the Panama shortcut. The majority of these prospectors that risked the terrain on the California Trail came by foot, wagon, stage, or horseback. The heart of the destination upon arrival to the west spanned a 300-mile trail between Oakhurst to Vinton, California, better known today as California Highway 49.

As news spread across the seas, the wealthier gold-seekers from other countries would take the quickest route to California by ship. They would sail to Central America and then cross the Isthmus of Panama. Travelers were exposed to diseases like malaria, yellow fever, and cholera. From Panama City on the Pacific coast, they would then negotiate their remaining travels by another ship willing to take them north to California. Many “Forty-Niners” never saw the end of the line despite their willingness to make the dangerous trip. With their odds against them due to the weather elements, unknown terrain, disease and a wilderness of nature as far as the eye can see, those who did stake a claim in California were the more fortunate ones.

Today, the branches of the California National Historic Trail system include approximately 5,665 miles of historic routes. Of this total mileage, approximately 1,100 miles of trail still exists as trail ruts, traces and other obvious remnants.

Preston maintained a copy of the California Agreement, which was received by John C. Ball, Porter County Clerk of the Courts, on April 3, 1849. John previously had been the LaPorte County Clerk in 1835 after he had been influenced by his cousin Dr. Seneca Ball, who had served as a Probate Judge and State Representative in Lake and Porter Counties to pursue that office. Dr. Ball had moved from LaPorte to Valparaiso in 1836 and brought John along with him. In August of 1842, John was elected Clerk of the Courts for Porter County and took office that following March. He served seven years as Clerk and then went on to serve as county Treasurer for three years.

Whether or not Edward Flinn made it successfully to California or not is unknown at this place and time. However, what has been preserved is the contract by these gentlemen, who together formed a partnership built on trust, hoping to strike it rich one day.

Reference: http://www.wikipedia.com; Porter County Clerk Archives, Porter County, Indiana; http://www.genealogytrails.com; http://www.britannica.com; http://www.listverse.com; http://www.ca.gov; U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management; National Park Services; http://www.history.com; http://www.legendsofamerica.com.