Written by Victoria Vasquez | June 28, 2024

Early Railway Construction

Railways began in the 17th century in England built to transport heavy loads before reaching the borders of North America. The first transport road was called a “gravity road” and it was used for military purposes at the Niagara portage in Lewiston, New York. Another early form of transportation track was known as a “tramroad.” The earliest map of a tramroad in the United States was drawn in Pennsylvania in October 1809 by John Thomson and was entitled “Draft Exhibiting . . . the Railroad as Contemplated by Thomas Leiper Esq. From His Stone Saw-Mill and Quarries on Crum Creek to His Landing on Ridley Creek.” Tramroads used horsepower to haul heavy loads across the unsettled frontier as more construction was being done to settle the unchartered territories of North America.

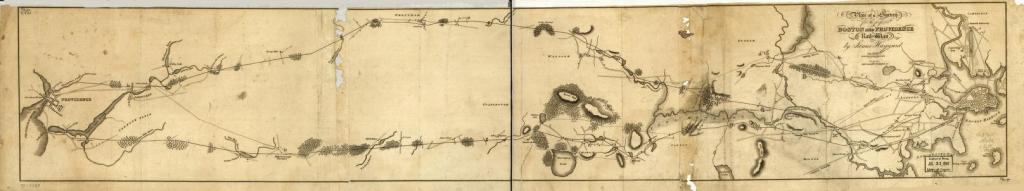

Many pioneers of the early railway system were surveyors, civil engineers, and wealthy businessmen. James Hayward’s 1828 plan of a survey for the proposed Boston and Providence Railway is the earliest topographic strip map in the Library of Congress that shows a railroad survey. The survey lines were originally intended for horse drawn trains.

Source: The Beginnings of American Railroads and Mapping; Library of Congress

In 1826, John Stevens, who is considered as the father of American railroads, demonstrated the innovation of using steam locomotion to move loads across the early tracks. He introduced this concept on a circular experimental track constructed on his estate in Hoboken, New Jersey, three years before George Stephenson perfected the practical steam locomotive in England. In 1815, Stevens secured the first railroad charter in North America. Grants to other railroad companies followed, and work soon began on the first operational railroads. The Baltimore and Ohio Railway Company started its construction of track in 1830 by surveying and mapping out fourteen miles of track that would open before the year ended.

By the 1840s, the railroad reached into the agricultural belt of the American Midwest. Between the railroad and the port of the Erie Canal, inland trade passed between the waterways and the connections leading to the Midwest. As growth and settlement expansions continued inward to lands further away from water canals, the need to have a solution for access to goods was becoming more critical to the survival of towns and homesteads. The first to take an active role was Baltimore, which in the 1820s had become the second largest city in America. On July 4, 1828, Baltimore merchants began the construction of a railroad from the harbour to a receiving point on the Ohio River. Other railroads, such as the South Carolina Railroad quickly emerged as more merchants came together to construct ways to get their goods across the vast land of the new frontier.

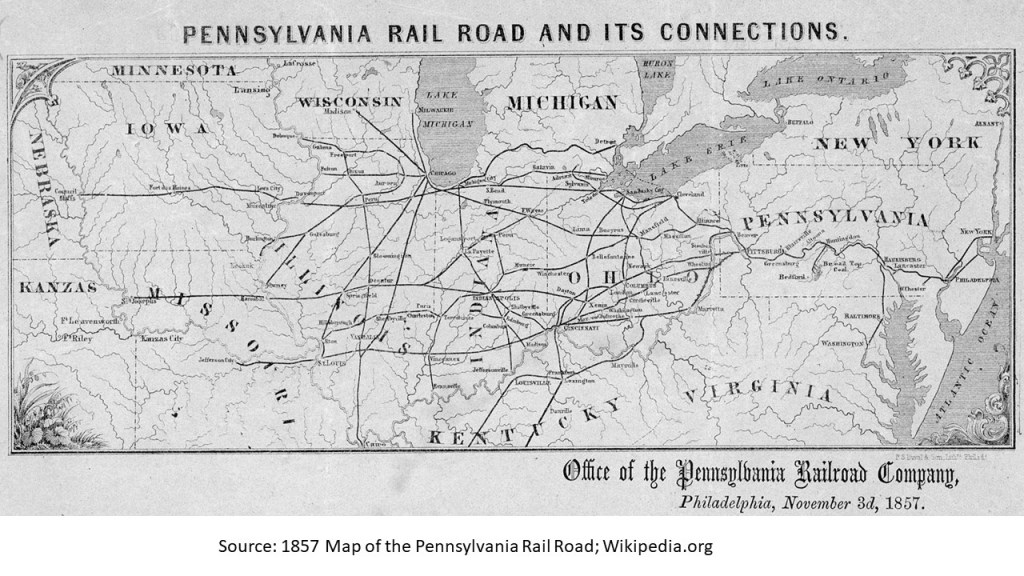

In 1852, the Pennsylvania Railroad reached Pittsburgh and began seeking ways to merge with other transporters for of second-phase railroad that would travel through the Midwest into a line from Pittsburgh to Fort Wayne, Indiana, and into Chicago. The Chicago exchange was considered the dominant junction point of the vastly productive agricultural and industrial Midwest region of the early eastern prairie states. The first railroad from the east reached Chicago in February 1852, and soon thereafter railway lines were built toward the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers.

Although the railways were built with the utmost purpose and intentions of accommodating settlers with goods of commerce and provisional stability, the industrial innovation of locomotive transportation did come at a hefty price, and sometimes that price was the cost of a life. Working on the railroad was a dangerous trade, from those who laid down the tracks to those who worked on the train; others found the excitement of chasing the train to catch a free ride or took on the challenge of chance with the uncertain speeds of the metal horse; but it’s the lives of the innocent victims of tragedy that shook the core of most hearts across the lands.

Rail Track Tragedies

David H. McClain (1891)

A brisk ride in a wagon turns into chaos when its driver failed to move his horses fast enough out of danger. During the morning of June 2, 1891 at 6:52 AM, David H. McClain was driving his wagon in Boone Grove when the Number 24 extra work train of the Chicago and Erie Railway was heading westbound on the track. William J. Guy, the engineer, had sounded the regular station whistle about one fourth of a mile east of Boone Grove. He then blew the whistle a second time roughly 10 seconds later for the regular crossing whistle upon approaching the depot to warn any travelers of the train’s approach. It was at that moment William saw a two-horse wagon and a man driving it about 40 feet ahead of the track heading toward him. William continued to blow the whistle again to notify the man of his danger. The engineer saw that the driver could not get across the track in time, but witnesses could not recollect if the engineer rang the train bell.

Guy saw that McClain tried to turn his horses to the right but the engine struck the left hind wheel of the wagon and the horse. William H. Laughlin was the conductor that day and recounted that the engineer tried to reverse the engine while he jumped to set the break. In the meantime, McClain was halfway across the tracks but it was too late. The engine, which was traveling at a speed of 15-20 miles an hour, struck McClain and his horse. McClain died about a half hour later.

Source: FiveMinuteHistory.com; Between 1815-1915, the horse and buggy was the primary means of transportation. This early depiction of a 19th century carriage was common until Henry Ford made automobiles affordable for the working class.

William Shultz [Shults] (1899)

On July 7, 1899 in Kouts of Pleasant Township, William Shultz lost his life while on a mixed train Number 182 of the Chicago and Erie Railroad at about 1:40 PM. William was the son of Cyrus Shultz, a prominent farmer of Morgan Township. An agent for the railroad saw Shultz attempt to get on the train at the station going north. This type of train does not stop at the station unless it’s for freight or passengers. Neither were required at the time of the incident. According to witness, O. H. Treadway, railway agent, the train was running from 10 to 12 miles an hour when he saw the deceased for the first time running along the platform on the east side. He tried to get on a coal car when he caught hold of it next to the caboose. He was about 10 feet south of the Erie Crossing when he did not notice the end of the platform and stepped off. The effects of his injuries received while attempting to board the moving train were life threatening. His right leg was crushed below the knee while the left leg was crushed two times below the knee from being dragged across the Erie track. William was brought to Kouts and then taken to the home of his father, where he died while attending physicians were amputating his limbs. He was 17 years old.

Source: Chicago Great Western Number 182 Train; Depiction of steam locomotive. The railroad of the Chicago and Erie Railroad Company extends northwesterly from Marion, Ohio, to the Indiana-Illinois State line near Hammond, Indiana. http://www.wikipedia.com.

Double Tragedy of Dr. Boris Borovik and Belle Drozdowitz (1920)

An inquest by Herman O. Seipel, Coroner of Porter County, State of Indiana was held on June 2nd 1920 in Center Township for the double tragedy that occurred on May 30, 1920 involving Dr. Boris M. Borovik and Belle Drozdowitz. Dr. Borovik was born in Russia and emigrated to the United States when he was 21 years of age, which was 49 years prior to his death. He studied dentistry at the Northwestern University Dental School where he graduated in 1900. He was a widower, once married to Sophia “Fannie” Schaffer. Little is known about his passenger, Belle Drozdowitz, other than she was the wife of Theodore Drozdowitz. Both victims were residents of Illinois. According to the deposition of witnesses, the automobile that both Boris and Belle were traveling in was struck by a westbound Pennsylvania Passenger train at about 11:43 A.M as it passed the Grand Trunk Crossing. In spite the train whistle blowing, the automobile seemed to be coming to a stop but slowed and started up again as it approached the crossing. The train was traveling between 65-70 miles an hour when it collided with the vehicle and instantly killed both passengers.

Source: Indiana GenWeb Project, Porter County. Depiction of the Grand Trunk Western Railway Station located at 801 Calumet Avenue next to Bush Street. Postcard by Dodge’s Telegraph, Railway Accounting and Radio (Wireless) Institute, (1924). Shook Collection.

Train Disaster at Porter, Indiana – 37 Dead (1921)

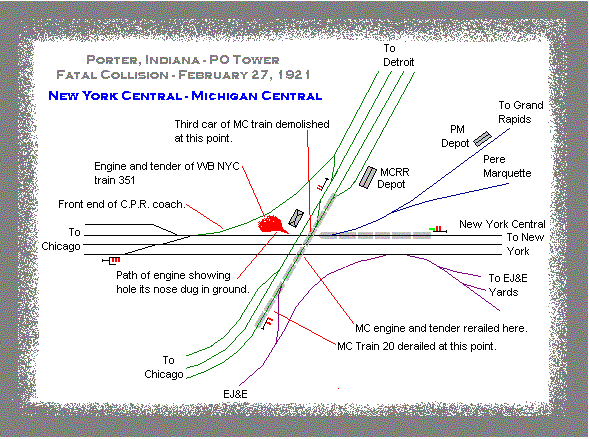

On Sunday evening, February 27, 1921, the westbound New York Central passenger train No. 151, known as the Interstate Express, was traveling on route to its destination in Chicago, which was due at 7:30 PM. Traveling eastbound was the Michigan Central’s No. 20, known as the Canadian, had left Chicago at 5:05 PM and was headed for Detroit and Toronto. The NYC train ploughed into the third coach of the Michigan Central at an interlocked crossing of the lines in Porter, Indiana. Since both trains were running at high speeds, the impact to the coach car turned it into a mass of kindling wood.

The Michigan Central train was due to arrive at Porter at 6:16 p.m. and was running a few minutes late at the time of the accident. The schedule time of this train is 50 miles an hour between Hammond, Indiana and Michigan City. The schedule running time of the New York Central train between La Porte, Indiana and Englewood (Chicago) Illinois is 41 miles per hour.

The General Manager of the Michigan Central Railroad, Henry Schearer, announced on March 1 that the company took full responsibility of the disaster after its investigation revealed that their engineer and fireman were to blame for the wreck. Schearer stated that:

“In the matter of the unfortunate collision at the crossing of the New York Central and Michigan Central railroads at Porter, Indiana, Sunday February 27, 1921, of New York Central Train 151 and Michigan Central 20, after a careful investigation of the facts with all interested employees and conference with officials just completed, it has been determined that engineer, William S. Long and fireman George F. Block on engine 8306, train 20, violated rules and regulations in failing to observe and properly obey signal indications and will forthwith be dismissed from service.“

Source: From Railway Age, March 4, 1921; New York Central passenger train No. 151 collision site with Michigan Central train No. 20; http://www.MichiganRailroads.com.

On March 21, 1921, the Interstate Commerce Commission’s Bureau of Safety in Washington, D.C. issued a report, which concluded the same findings announced by Henry Schearer of the Michigan Central Railroad. The report found fault in Engineer Long and Fireman Block for Long’s failure to observe and obey track signals and for Blocks’s failure to properly identifying the signal and conveying the correct information to Long.

The day following the wreck, Herman O. Seipel, Porter County Coroner, announced that 37 individuals perished in Chesterton, Westchester Township, Indiana as a result of the collision. More than 100 injuries were estimated in the casualties of the disaster. The March 1921 issue of the Railway Signal Engineer stated that:

”One peculiarity of the accident is that those killed were mostly decapitated, a number being mutilated so badly that identification was next to impossible.”

After the accident Engineman Long of the wrecked Michigan Central train was reported as saying: “My fireman, Block, first sighted the signal that meant a clear track and called my attention to it. We were running a full speed and did not slow down when we were certain the signal was right. Proof that we were not to blame for the wreck is seen from the fact that the engine and one coach passed the derail. I will not state what I believe caused the wreck. The derail was locked and I could not be to blame.”

Joseph Cook, the leverman on duty at the interlocking plant at the time of the accident, declared after the accident that Engineer Long ran by the home signal. The New York Central train was given the first right to pass, as it approached its route and had initially announced it was coming by the indicator in the tower. Cook stated, “Under normal conditions the block is set against all trains. The train hitting the buzzer first is then given the right of way. That is exactly what happened when the buzzer sounded yesterday. It showed that the New York Central train was the first to hit the buzzer by almost a full minute ahead of the Michigan Central flyer.”

He continued, “I released the block which permitted the New York Central train to go through. Just as the train hit the crossing, I saw the Michigan Central train coming around the curve at 60 miles an hour. I saw right away what was going to happen and thought the tower would be demolished. I called to Charlie Whitehead, the telegraph operator in the tower with me, and made for the steps which lead to the ground. The Michigan Central train by this time had hit the derail, which clearly showed that the block had been set against it and plowed over the ties and track, tearing them up as it went across the New York Central track. When the third coach of the Michigan Central train passed over the New York Central right of way the New York Central train cut through it. As the locomotive of the New York Central train passed over the track it toppled over and the coaches of both trains were scattered in all directions.

Source: Chicago Daily News published February 27, 2021; Library of Congress Collection.

The Interstate Commerce Commission issued a report, dated March 14, and signed by W. P. Borland, chief of the Bureau of Safety, on the train wreck. The report concluded that the engineman of Michigan Central No. 20 saw and heeded the cautionary indication; reduced speed from 60 miles an hour to perhaps 50 miles and took the word of the fireman that the home signal indication was clear.

It was further reported that “The direct cause of this accident was the failure of Engineman Long to observe and obey the signal indication of the home signal. A contributing cause was the failure of Fireman Block properly to observe the home signal indication and convey the correct information to Engineman Long. The evidence indicates that Long relied practically, if not entirely upon the announcement by Block of the indication off the home signal instead of observing it himself. The location of the signals is such that it was both possible and convenient for him to observe the signals personally and for his failure to do so there is no excuse. Even if he did confuse the train order signal with the top blade of the home signal, he still did not receive a proper indication to proceed at normal speed, as his movement was also governed by the train order signal, the indication of which he was required to observe before passing it.”

In the end after many search efforts while crowds gathered from far and wide to witness the wreckage, the final casualties recorded included thirty-five (35) passengers and two (2) employees killed and eleven (11) passengers, two (2) employees and seven (7) other persons, who were injured.

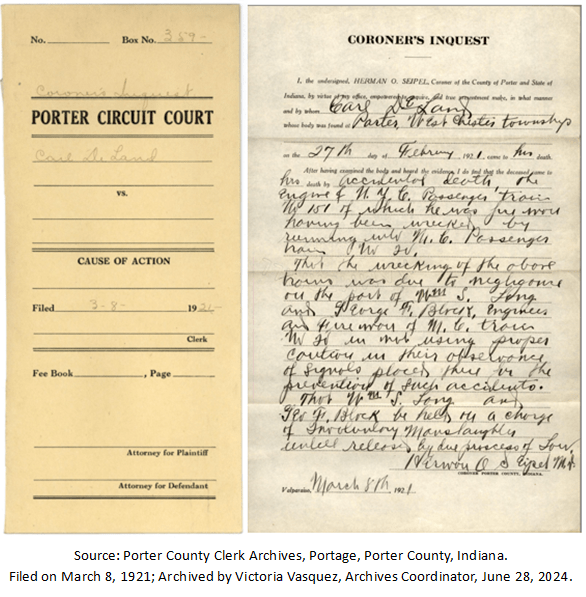

Herman O. Seipel, Porter County Coroner, stated in his coroner’s inquest of Carl Deland, and repeatedly in others, the following:

“After having examined the body and heard the evidence, I do find that the deceased came to his death by accidental death, the engine of N.Y.C. Passenger train No. 151 of which he was fireman having been wrecked by running into M.C. Passenger train No. 20. That the wrecking of the above trains was due to negligence on the part of Wm S. Long and George F. Block, engineer and fireman of M.C. train No. 20 in not using proper caution in their observance of signals placed there for the prevention of such accident. That Wm S. Long and Geo F. Block be held on a charge of Involuntary Manslaughter until released by due process of law.” -Howard O Seipel M.D., Coroner Porter County, Indiana.

The Chesterton Tribune printed the names and hometowns of the 37 individuals that perished in the disaster, as provided below. The use of cemetery and death certificate information allowed for any name corrections in spelling at the time of its report.

However, due to new evidence discovered by Victoria Vasquez, Archives Coordinator of the Porter County Clerk Archives, there is at least one discrepancy on the list which is cause for correction in the history annuals. George Deland is listed as the fireman of the New York Central train, yet the name on the original Porter County coroner’s report identifies it as Carl Deland. The coroner’s report clearly expresses that Carl was the fireman on the New York Central Passenger train, Number 151.

According to a news article in the Elkhart Truth published on March 2, 1921, pg. 2, Rev. F.C. Berger, pastor of the First Evangelical church, officiated the funeral sermon for Carl E. Deland. Berger affirmed in his sermon that Carl was killed in the Porter disaster. He recalled how Carl started out as a railroader at 17 years of age and had worked his way from a yardman to passing an examination as engineer. Carl was a member of Prospect lodge of the B. of L.F.&E. and is at laid to rest at the Rice Cemetery in Elkhart, Indiana.

In remembrance of…

ARNEY, Howard – Cleveland, Ohio (age 35)

ARNEY, Mrs. Katherine – Cleveland, Ohio (age 35)

BAEHR, Lillian Anderson – Michigan City, Indiana (age 28)

BAKER, Joseph L. – El Paso, Texas (age 23)

BEVIER, Mrs. Emma – Augusta, Michigan

BEVIER, C. A. – Augusta, Michigan

BALLOU, Fannie L. – Wheatfield, Illinois (age 34)

CAIN, Peter Richard – Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada (age 34)

CAMPBELL, Eva June – Jackson, Michigan

CAMPBELL, William Gordon – Revelstoke, British Columbia, Canada (age 18)

COLLINS, Justin – London, Ontario, Canada

COLLINS, Alexis – London, Ontario, Canada

CAVANAUGH, Pearl – Michigan City, Indiana (age 9, niece of Mrs. Ralph See)

DELAND, George – Elkhart, Indiana (fireman on New York Central train)

EKMAN, Arthur Elmer – no hometown listed (age 2)

ENGLER, W. G. – Detroit, Michigan (age 30)

FLEMMING, Florence Philo – Kalamazoo, Michigan

GOLDSTEIN, Phillip H. – Detroit, Michigan (age 29)

GOLDSTEIN, Martha – Detroit, Michigan (age 28)

GREENWOOD, Dr. Ray E. – Kankakee, Illinois (age 28)

HECK, Louis A. – Jackson, Michigan

HOSKINS, Theodosia J. Mason – Chicago, Illinois

JOHNSTON, Claus – Elkhart, Indiana (age 48, engineer on New York Central train)

KRAMER, Rose Henoch – Michigan City, Indiana (age 58)

LANGIN, Augusta B. Zimmerman – Cleveland, Ohio

LANGIN, Mrs. Dorothy H. – Cleveland, Ohio (age 18)

LIVINGSTON, Samuel – Chicago, Illinois (age 38)

MOSS, Mrs. Sarah – Montreal, Québec, Canada

MULLER, John L. – Crescent City, Illinois (age 62)

MULLER, Friedareka Kohlmetz – Crescent City, Illinois (age 48)

SCHWEIR, Frances Retseck – Michigan City, Indiana (age 31)

SCHWEIR, Richard – Michigan City, Indiana (age 3, son of Mrs. Fred Schweir)

SEE, Florence A. Leffel – Michigan City, Indiana (age 38)

VAN RIPER, Alvin H. – Michigan City, Indiana (age 69)

VAN RIPER, Aminta May Dahlson – Michigan City, Indiana (age 55)

WAGGONER, Lillian Johnson – no hometown listed

WAYNE, Frank – Milwaukee, Wisconsin (age 49)

References: Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov; Brittanica.com; Porter County Clerk Archives, Portage, Indiana, http://www.clerkarchives.in; http://www.ancestry.com; http://www.findagrave.com; http://www.michiganrailroads.com; http://www.porterhistory.org;