Written by Victoria Vasquez | July 31, 2024

FIRE IN THE SKY

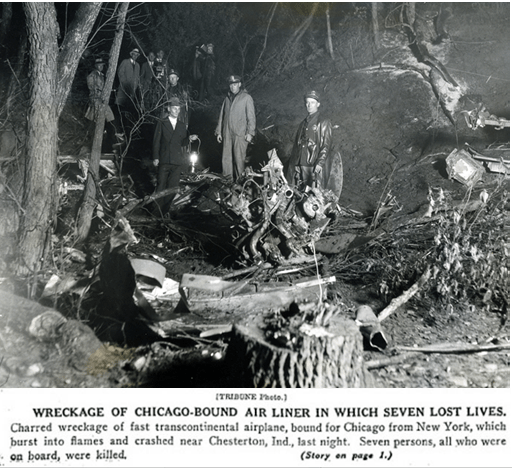

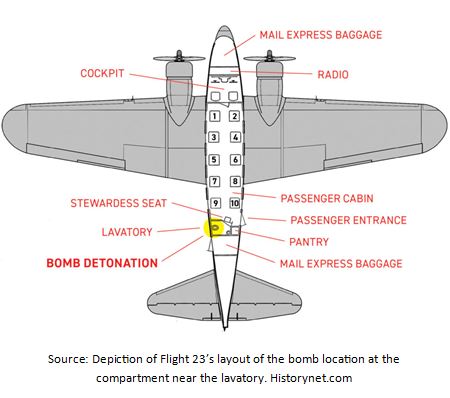

On October 10, 1933, witnesses watched the sky in disbelief. Dr. Carl Davis, Porter County Coroner, had a grave task to tackle and it would be a first of its kind. The tragedy of United Airlines Flight No. 23, a Boeing 247 registered as NC13304 came crashing down onto the borders of Chesterton, Indiana. Government aeronautical inspectors and United Airlines officials had their opinions on the cause of the explosion. While some local witnesses said that the airplane burst into flames in the air while operating with 1 motor then plummeted 1,000 feet to crash, airline officials doubted those reports and instead believed that the airplane drove into a hillside and exploded there. One certain speculation made was that a bomb had been loaded onto the big twin motor airplane into either the lavatory or the baggage compartment leaving its passengers helpless in their defense.

Four crew members and three passengers perished in the flight that departed New York and was bound for its final destination in Oakland, California. It had refueled in Toledo, Ohio before heading towards Chicago. One witness account indicated that one of the passengers was seen carrying a brown package onto the plane in Newark then got off the plane, but investigators ruled the package out as being the cause of the explosion. A second notion for the explosion was a rifle that was found in the wreckage but it was later determined that it was carried aboard by a passenger on his way to attending the Chicago North Shore Gun Club.

The silver-gray Boeing 247 No. 23 was an aviation innovation compared to its predecessors. Its sleek all metal construction was made of anodized aluminum, a fully cantilevered wing, and retractable landing gear. Boeing created the 10-passenger aircraft exclusively for United Airlines. With 7 years of flight operations to its name, the United Flight No. 23 plane had logged over 60,000 miles with its 2 experienced pilots at the helm. During the investigation, United Airlines disclosed that the pilots had radioed minutes before the explosion that “all was well.” Little did they know their fate was about to change.

Great lengths were taken to recover the bodies. The last 2 bodies were found 12 hours after United Flight No. 23 plunged to the earth bursting into roaring flames. They had been thrown 250 yards from the cabin section near the broken tail of the plane. The crash scene was adjacent to a gravel road about 5 miles outside of Chesterton, centered in a wooded area on the Jackson Township farm of James Smiley. Pilot Captain Tarrant, Co-pilot Ruby, flight attendant Alice Scribner and all passengers were killed. Scribner was the first United flight attendant to be killed in a plane crash.

Dr. Carl Davis, Porter County Coroner and experts from the Crime Detection Laboratory at Northwestern University examined evidence from the crash. Their review of the excessive damage and outward explosive pattern helped them to conclude that the United Airlines Flight No. 23 had been bombed. Newspapers across the nation carried the stories of this first aviation sabotage on U.S. soil.

Dr. Carl Davis was born June 19, 1896 in Logansport, Indiana, USA, and died on May 1, 1981 in Lafayette, Indiana, USA. Carl is buried in Graceland Cemetery in Valparaiso, Indiana. He received his B.S and M.D. degrees from Indiana University.

“Coroner Carl Davis of Porter county said today the possibility of a time bomb having wrecked the United Air Lines New York – Chicago plane was under investigation. The plane fell near here Tuesday night, killing seven persons. Dr. Davis had returned an open verdict holding the cause of the crash was unknown. He said today, however, he was convinced there was an explosion aboard the plane. He did not reveal the basis for the inquiry into the possibility of a time bomb having wrecked the air craft. Further inquiry is also being made, the coroner said, into reports that a gun of high power was in the baggage of Emil Smith of Chicago, one of the passengers. The coroner was informed that Smith, a retired grocer, was returning from New York to Chicago to attend a shoot at the North Shore Gun club.” — Prescott Evening Courier — October 12, 1933

A crime laboratory, whose creation was in response to Chicago’s St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, played an integral part during the investigation. United Airlines officials had provided details on their theories to investigators as they developed.

“Dr. Muehlberger’s findings, according to United Air Lines officials, centered upon a piece of blanket, part of the plane’s equipment, and several pieces of the metal surface of the plane. Both had been pierced many times by small bits of metal. Only a high explosive could produce a force great enough to force metal through metal, Dr. Muehlberger said. He turned down the theory of a gas explosion, because, he said, gas expands comparatively slowly and would not produce such terrific force.”

THE INVESTIGATION

After combing through the debris, investigators were confronted with unusual evidence: the toilet and baggage compartment had been smashed into fragments. Shards of metal riddled the inside of the toilet door while the other side was free of the metal fragments. The tail section had been severed after the toilet and was found mostly intact almost a mile away from the main wreckage.

Melvin Purvis, head of the Chicago office of the United States Bureau of Investigation described the damage, “Our investigation convinced me that the tragedy resulted from an explosion somewhere in the region of the baggage compartment in the rear of the plane. Everything in front of the compartment was blown forward, everything behind blown backward, and things at the side outward. […] The gasoline tanks, instead of being blown out, were crushed in, showing there was no explosion in them.”

Finding a suspect was slim and the investigators had their work cut out for them. However, they did rule out the possibility of any passengers being the bomber. The passengers on board Flight No. 23 were cleared of any wrong-doing. Those removed from the suspect list were the following:

Dorothy M. Dwyer, a woman from Arlington, Massachusetts

Emil Smith, a man from Chicago, Illinois

Fred (C. F.) Schoendorff, a man from Chicago, Illinois

“A few minutes before 4:30 p. m. one day last week at Newark Airport, United Air Lines’ ten-place transport No. 23, bound for Chicago, taxied up to the passenger depot for loading. The passenger list was unusually small. There was a trim young woman who, flushed with excitement, confided in the pilot that she had missed the previous plane and had to be in Reno next morning ‘to visit her sister.’ (It turned out that she was to be married next day.)” — TIME Magazine, October 23, 1933

Metropolitan Newsreel Photo of 1933

Emil Smith was also cleared of suspicion. Although he was the one who brought a rifle onto the plane, investigators agreed that it was not likely for him to use the rifle for any cause prior to blowing up a plane; and finally, the last passenger under the microscope was Fred Schoendorff, who at the age of 28 years old, appeared unlikely of carrying out such an attack. He was an apartment manager with a spotless background. Police cleared him of any suspicion. Beyond the passengers, the flight crew was also ruled out as suspects. They lost their lives in what would be the first recorded bombing in aviation history. The crew members who perished were as follows:

Captain H. R. Tarrant, Oak Park, Illinois — the pilot (male)

A. T. Ruby, of Chicago, Illinois — the copilot (male)

H. R. Burris, of Columbus, Ohio — the radio operator (male)

Miss Alice Scribner, of Chicago, Illinois — the flight attendant (female)

SEARCHING FOR ANSWERS

Investigators hit a dead end after years of searching and coming up empty. To date, no one knows who was responsible for the bombing of United Airlines Flight No. 23. And if someone does know, they aren’t talking. Bits and pieces of new evidence have surfaced over time and investigators have considered them with care. Theories have ranged starting with the crew or passengers being the culprits of the explosion, and then to the speculation of a labor dispute between United Airlines and their pilots. And a final theory to have suspected mafia gangland type of activity with Chicago or New York, yet this was never proven. Investigators didn’t have any leads to connect the mafia kingpins to the explosion.

The last piece of evidence was recorded in 1999 when an old man named Howard Johnson recalled that he had driven to the scene of the accident in his Ford Model T. He went on record stating the details of that time, which was captured during a history project led by the Westchester Public Library located in Northwest Indiana.

“No, I guess it had something to do with some labor racketeer because they said that– It was all rather vague but they said that someone got on the plane in Cleveland and had a suitcase and then they got off and no one saw them take the suitcase off. So that’s no doubt what happened. They just left the bomb on the plane.” -Howard Johnson, oral recount.

On November 16, 2017, the Federal Bureau of Investigation declassified 324 documents related to the investigation.

The bombing of United Airlines Flight No. 23 remains an unsolved mystery.